-

I have Parkinson’s Disease

Yep, I have Parkinson’s Disease.

I was diagnosed on August 14, 2018 – four years ago.

I’ve kept it secret all this time.

Only a few close friends know.

My mother, and my mother-in-law, don’t know,

nor one of my sisters.I first noticed symptoms about 12 months before I was diagnosed.

Loss of smell, tremor in my dominant hand, small handwriting, a weakening voice, a stooping posture and shuffling gait. I consulted Dr Google, and it all pointed towards Parkinson’s. So when the neurologist – one of the best in the country – told me, I wasn’t surprised.

For the first year after I was diagnosed, only my wife Jennifer knew. After twelve months I told my children. For two years I went without medication – but it started to seriously mess with me and so I finally asked to be medicated. And the medication has helped hugely.

Why did I keep it secret for so long?

Because I didn’t want people judging me, labelling me, putting me in a box called “Damaged Goods.” I didn’t want it to affect my career. I wanted people to say: This is Bill Bennett, the film director. I didn’t want them to say: This is Bill Bennett, he has Parkinson’s Disease. The film industry is very judgmental.

Okay then, so why am I making this public now?

Well, an article came out today in the Fairfax publications, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, in which I discuss how the fear associated with learning of my disease informed my new film, Facing Fear, soon to be released.

Here’s a link to the article: Filmmaker Facing Fear.

How am I now after 4-5 years with this disease?

I’m doing okay. I’m doing all those things I’m meant to do to slow the progression of the disease – I’m exercising regularly and intensively, I’ve changed my eating habits, and most importantly I’m thinking the right way.

I’ve refused to accept that I’m sick – that I have an incurable brain disease. I’m getting on with life – at full steam. I have a lot to do before I can’t.

I don’t see this as a bad thing.

I see this as a gift.

-

My new Blog:

I’m starting a new blog. It’s called BillBennett.blog

Original, huh?

I started blogging nearly ten years ago when I walked the Camino de Santiago. That blog was called PGStheWay.

It became popular and I kept it running, and it gradually morphed into a blog not so much about the Camino as about what I was doing in other areas of my life – such as making films and writing books and traveling.

But also it became a way for me to write about things that were of interest to me. PGStheWay though kind of ran out of puff – so I’ve decided to put it to bed, pull up the covers on it, and gently turn out the light and close the door.

I’m thinking I’ll publish a book of the most interesting blog posts. There’s some good stuff in there amongst the nearly thousand posts I published.

(Previous followers of mine will note that I am not limited or constrained by abject humility…)

Anyway – I just wanted to let you know that I will be posting regularly here every week, and sometimes more than that if something comes along that I feel needs examining.

I’ll be updating what I’m working on – the new film on fear coming up, and the new novel called The Golden Bridge which will be published later next year. I’ll be revealing the publisher, and posting excerpts.

I’ll also post pics – I love taking pics – so please do follow me here on this blog, to make sure you get the posts straight out of the chute!

I’m very excited to be starting out afresh!

-

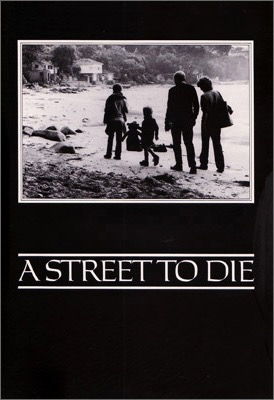

The story behind A Street to Die ~

A grand old cinema in Sydney, the Ritz in Randwick, is celebrating its 85 yr anniversary, and to mark that milestone they’re screening a bunch of classic Aussie movies.

One of the films they’ve selected to screen is my very first feature film, A Street to Die, which I made in 1983-84. I was 30 yrs old when I made that movie.

I thought I’d give you the story behind the movie, and how it got made ~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A Street to Die was my first feature film which I began to make in 1983. I’d been married to Jennifer Cluff for a year, and Jennifer had just given birth to a beautiful little girl, Nellie. I’d set myself up as an independent producer a year earlier, and had made two 50 minute dramatised documentaries, one of which had just won the Sydney Film Festival Award for Best Documentary. Both films had been picked up on completion by the ABC and the BBC.

Prior to making those two films, I’d spent ten years at the ABC where I trained as a journalist, then I moved into current affairs as a reporter/producer (This Day Tonight and Four Corners), and from there I moved into producing and directing documentaries for the ABC’s flagship show, A Big Country.

I’d wanted to move into drama for sometime, because I found documentary very limiting. I tended to want to mess with reality, which is a big no-no in documentary. So while making docos I took up acting classes, to learn how to direct actors. I felt that was essential if I was to become a feature film director. More on that later.

I remember one Saturday morning, I was having breakfast and reading The Weekend Australian. There was a front page story about a street in the western suburbs of Sydney that had housing for war service veterans.

What was remarkable about this street was that on one side there were houses for Korean veterans, and on the other side was housing for Vietnam veterans. The front page story was largely taken up with an aerial photograph of the street, showing that almost every house on the Vietnam veterans’ side had major health problems – cancers, miscarriages, suicides, respiratory issues – yet there were no really serious medical issues on the Korean side.

The story featured a piece about Colin Simpson, a Vietnam vet who had come down with Lymphoma which he believed was caused through his exposure to Agent Orange. Colin Simpson had been a forward reconnaissance soldier, and he often went behind enemy lines into areas that had recently been defoliated by Agent Orange. On several occasions, he was actually in the jungle when planes flew overhead and dropped Agent Orange onto the foliage in which he was hiding – soaking him.

The newspaper story was about how Colin Simpson, who worked as a printer at one of the big newspaper conglomerates, decided to take on the Federal Government because he believed that there was a causal link between his cancer and his exposure to Agent Orange.

At the time, no Government involved in the Vietnam War had acknowledged culpability for their use of the deadly chemical.

Colin Simpson, a working class bloke, threw himself into detailed research and took the Government to court. He was knocked back two times but repeatedly appealed, and he died before the third appeal was heard. His wife took that third appeal to court and subsequently won – and it was the first time that a government had been forced to acknowledge a link between the death of a veteran and their military’s use of Agent Orange.

It became a major precedent case around the world.

So I read this remarkable story while having my brekkie and it really stirred a fire in me. I thought immediately that there was a film in it. This was a story that had to be told on a wider canvas. So I sent a researcher out to the street to spend time with Colin Simpson‘s wife. After three weeks the researcher came back and said: You must do this film.

Over the next several months I worked very closely with Colin Simpson‘s wife on the writing of the script. She had script approval at every stage. And she even decided to allow us to shoot the film in her actual house.

First though, I had to get the film together. I had to cast, and then I had to raise the money. I wasn’t prepared to go to a producer – I knew from past experience that they’d just dick around and juggle my precious project with several others, and I’d spend years waiting for them to pull it together, if indeed they ever would. So I decided to produce it myself. After all, I’d just written, produced and directed two 50 minute dramatised documentaries – how difficult could it be to do the same on a feature film?

I was soon to find out!

From very early on I had Chris Haywood in mind to play the role of Colin Simpson. Not only was Chris renowned at that time as being a larrikin and a quirky character, I was also very aware that he was a wonderful actor. I’d been a big fan of his work for some time. He had all the attributes to play Colin Simpson.

Chris took on the role and threw himself into research. He spent a lot of time with Colin‘s mates at the printing factory, and also with his wife. He got all of Colin Simpson‘s mannerisms and ticks down, even such details as how he lit his cigarette, how he smoked, and how he constantly jiggled his leg.

Meanwhile I had to raise the money to make the film.

I had not been successful in getting any government money from previous efforts on other productions – I’d constantly been knocked back – so with this one I didn’t even try. It would be a total waste of time. So I decided to try and raise the money privately.

I got some brochures printed out, and I headed north to Queensland because I heard the farmers up there had had a bumper year with sugar cane prices – so that’s where I headed.

I flew from Sydney to Rockhampton, hired a rental car, and hunkered down in a cheap motel in Rocky. I then got the Yellow Pages phone book, looked up Accountants, and phoned each firm saying I was a film producer asking if I could come and see them to talk about a project. Some gave me a flat NO, but some agreed to see me.

I saw about six different accountants in Rockhampton, and with each one I gave them a pitch about the film, the tax breaks associated with film investment, and made sure to mention that I’d just recently won the Sydney Film Festival Award. That was the only thing I had to trade off – I’d never made a full length feature film before, I had no track record, I had no distribution for the film, no presales, nothing. All I had was a good story and a lot of passion.

They all listened politely, some asked a few questions, some said they would pass all the details onto one or two clients that might be interested. That was it. Nothing more. No signed investment contracts, no signed cheques, nothing.

So I checked out of my cheap motel and drove north, to the next big town – Gladstone. I did the same thing there. Checked into a cheap motel, got the Yellow Pages, made appointments to see those accountants willing to see me. I did the same dog-and-pony show, left brochures, drove out of Gladstone a few days later with no real prospect of investment.

I worked my way up the entire coastline of Queensland, visiting smaller towns and the larger cities too – all the way up north of Cairns to Port Douglas. Each place I stopped I used the Yellow Pages to seek out accountants, I went and saw them, did my pitch, left brochures and moved on.

It took me three weeks and 1200 kms to get to Port Douglas. And still no investors. I returned to Sydney with nothing. Not one penny of investment.

I have to say at this point, Jennifer and I had no money. We were using the meagre fees I’d made on the two documentaries to finance this endeavour, and that money was fast running out. We had a young bub, we were struggling, but Jennifer was fearless. She backed me all the way – and in fact she’s continued to do that my entire working life, no matter what the challenges.

Anyway, I had a small office in a shopping mall beside the public toilets, and each day I made calls to those accountants who had shown a modicum of interest – some had offered glimmers of hope – but still no investment. And there was a ticking clock – under the tax laws at that time investment in film production had to be lodged by June 30th otherwise you effectively had to wait another twelve months to raise funds again.

At the beginning of June of that year we still had nothing – so here’s what I did. I flew again to Rockhampton, I went and saw those accountants that had deigned to see me originally, and I did the pitch again. I then drove to Gladstone, did the same there, then worked my way up the coast to Port Douglas, seeing all the accountants in all the towns a second time. It cost Jennifer and me a small fortune.

At the end of that trip, I’d raised $350,000 which was enough for me to make the film. This was in 1983.

A year earlier I’d met Jennifer Cluff at acting classes. She was already an accomplished actress, having played one of the starring roles in the ABC’s classic TV series Seven Little Australians. She played the role of Judy. She was doing acting classes kind of as a refresher course. I was doing acting classes because I wanted to move from documentary into drama and I believed I needed to know how to direct actors.

The acting coach was Brian Syron – at the time, one of Australia’s best acting teachers. He’d recently arrived into this country from New York, where he’d been assistant to the legendary Stella Adler.

I met Jennifer at this class and I asked her out on a date . Four months later we were married. We’ve now been married 40 years.

When considering who to cast opposite Chris Haywood as Colin Simpson’s wife, I didn’t hesitate in casting Jennifer.

The other great creative decision I made with that first film was to bring on Geoff Burton as DOP – Director of Photography. Geoff was legendary even in those days – having been DOP on some of Australia’s great movies, including Sunday Too Far Away, Storm Boy, The Picture Show Man, and many others.

Even after doing those two dramatised documentaries I knew that I knew nothing about making a feature film, and I knew that I needed an experienced hand like Geoff to help guide me through – which is what he did. Geoff taught me so much during the making of that film.

I can’t remember a great deal about the shoot itself, other than I think I was probably an arrogant pretentious know-it-all shit. At times it was very tense because we were recreating the life of this hero in the house where he lived, and Chris even wore some of Colin Simpson’s clothes. This put an enormous strain on Colin Simpson’s widow. She saw Chris every day ostensibly the living reincarnation of her deceased husband, and she had something of a breakdown, understandably.

I do remember though that Chris completely inhabited the skin of this man Colin Simpson – and Jennifer too became the very embodiment of his wife. When I think back on it now, I really didn’t know first thing about filmmaking – I did it all on instinct.

When the film was finished I brought on board a sales company– J C Williamsons – to handle foreign sales. They submitted the film to various film festivals – I didn’t have a clue how any of that worked – and one of the festivals that wanted the film was the London Film Festival.

I decided to attend. It was my first experience at a film festival. I’d never been to one before, even as a viewer.

The first screening at the London Film Festival went well. There was a big crowd and applause at the end. After the screening I walked outside the cinema and was immediately accosted by a fat man in a grubby creased suit. I remember he had food stains down the front of his shirt. He was a New Yorker, from his accent, and he spoke at a hundred miles an hour. He was a distributor – I figured he probably handled porn films – but he was passionate about the movie.

He said he wanted to take the movie on for US distribution. He kept saying very kind things about the movie, but I couldn’t stop staring at these food stains on his shirt. Also he hadn’t shaved and despite his obvious and very real passion for the film, and all his promises for what he could do to get the film out to American audiences, I finally decided not to go with him, principally because of the food stains down his shirt.

His name was Harvey Weinstein.

I’d never heard of the guy.The film subsequently screened at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival in the Czech Republic, and won the Crystal Globe for Best Picture, along with the Critics Prize. I didn’t realise at the time but the Karlovy Vary Film Festival was one of Europe’s top arthouse festivals, and winning the Crystal Globe was a big deal.

Back in Australia the film got six nominations at the Australian Film Institute Awards – I got three of those nominations for Best Film, Best Director and Best Original Screenplay. Chris Haywood won the AFI for Best Actor – and Jennifer should have won for Best Actress because her performance was extraordinary.

The film ended up selling everywhere. The investors got their money back, plus some, and the film launched my career.

Some time back now, the National Film and Sound Archives contacted me to say that they wanted to do a full digital remastering of the film – they wanted to include it in their 100 most significant Australian films.

This will be the version that will be screening at the Ritz cinema at 4 pm on Saturday, 27 August. There’ll be a Q&A after the screening. Jennifer, Chris Haywood, Geoff Burton and I will be there to answer any questions.

You can get tickets here…

https://www.ritzcinemas.com.au/movies/35mm-a-street-to-die-1984

-

I’ve become a gamer!

I’ve become a gamer.

Me, at my age. Coming on seven decades on this planet.

Yes, I now play video games and I’ve become obsessed.

I used to think that playing video games was a senseless waste of time. Why not use that time to read a book? Or write a book?

Why not use that time to watch a great show on telly. Or watch the Swannies, or a game of cricket. Now that’s not a waste of time. Watching The Ashes for six hours a day for five days straight. That’s certainly not a waste of time.

I don’t know what triggered me to start gaming. It was a few months ago now, and I went to my son, Henry – my eldest son – and asked him what do I need to do to start gaming.

Henry is a walking Wiki on gaming. He’s been a gamer most of his life. I could never understand it. I always used to think he could be using his time more productively.

Now I think differently.

Now I realise that gaming is a form of storytelling that is totally unique unto itself. Gaming tests and challenges you on so many levels. I now realise that watching sport, even reading a book, is passive, while gaming is active. Participatory.

Not to mention the art, the music, and the genius of designing games that take you to places that other more conventional forms of storytelling – even films – can’t possibly venture into.

I knew nothing about gaming when I started. I installed Parallels into my Mac laptop so I could use Windows to access games off Steam, a website that sells games. I bought a controller and a mouse and I had to get Henry to tell me what all the buttons were for on the controller.

You have to understand, up to that point I had zero knowledge of, or interest in, gaming. All my life I’d been sniffy about games, and gamers. But suddenly I became immersed in Journey, my first game. It was transcendent. Deeply mystical, a work of real art. It didn’t surprise me when I discovered that the game was featured in the New York Museum of Modern Art.

Here’s a YouTube trailer for Journey – LINK

Journey I began to seek out more games like Journey. I discovered a whole world of wondrous storytelling such as Ori and the Will of the Wisps, Myst, Monument Valley, Samorost, What Remains of Edith Finch, and others.

But I’ve also begun playing Dirt Rally, Portal 2, Hollow Knight, and Henry has even put me onto Hitman, Mass Effect, Grand Theft Auto and Skyrim. Great fun, but boy are they challenging.

Many of these games are way above my current skill level, which can best be described as baby trainer-wheels – but I’m eager to learn. I have a birthday coming up soon and I’ve asked my family to buy me a Nintendo Switch, so that I can play Zelda: Breath of the Wild. I believe it’s magnificent.

Not long ago I found an academic treatise on video gaming as art, published by Oxford University Press, called Games: Agency as Art, written by C Thi Nguyen – a Professor of Philosophy at Utah University. Here’s part of the Amazon blurb on the book:

C. Thi Nguyen argues that games are an integral part our systems of communication and our art. Games sculpt our practical activities, allowing us to experience the beauty of our own actions and reasoning. Bridging aesthetics and practical reasoning, he gives an account of the special motivational structure involved in playing games. When we play games, we can pursue a goal, not for its own value, but for the value of the struggle. Thus, playing games involves a motivational inversion from normal life. We adopt an interest in winning temporarily, so we can experience the beauty of the struggle. Games offer us a temporary experience of life under utterly clear values, in a world engineered to fit to our abilities and goals.

I’m reading the book at the moment and I’m realising that gaming isn’t a senseless waste of time after all. It’s a legitimate art form that can bring benefits not possible from other art forms.

Not only that, but in my taking up gaming it’s brought me much closer to my son, Henry. And you know what? It’s worth it just for that alone…

Playing Journey -

The Green Car of Fear – Jennifer’s perspective ~

Jennifer was in the car with me on Wednesday when we nearly died in a head-on collision. Here is her view of what happened:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I was dosing and I heard Bill say “Bloody hell”, and I snapped open my eyes and I saw a car on our side of the road, a green car, heading straight for us going extremely fast.

Bill quickly swerved around it, I don’t know how he did that because the road was very narrow, it was a small country road and he had very little room for manoeuvring, because it had guideposts all the way along the side.

The whole thing was all over in seconds, I didn’t have a time to even go into any form of panic. Then I worried about Bill because I thought: Oh my God, he must be in panic, but he seemed extremely calm.

My first thought once it was over was: Oh, we just had a head on collision and we’re dead and now we’re in heaven. Everything’s calm and beautiful, the sun is shining, everything’s beautiful around us, everything’s peaceful, everything’s perfect.

I said to Bill: Did we just die and go to heaven? And he said: Maybe. Then I said: That car was green, did you notice that? That car was the same color as our film?

Bill said that he did notice that.

It wasn’t a new car, it looked like a car that somebody had probably hotted up. It seemed to be quite low to the ground, and it was a green you don’t often see. It was a strange limey green color that I’ve only ever seen in the poster and artwork for Facing Fear.

When I first saw it it was coming at us extremely fast. I don’t know what the distances were but it was almost on top of us, it seemed, and it didn’t slow down in any way. It did not go: Oh oh, I should duck back in or anything, it just kept on coming, totally coming for us.

I don’t know how Bill maneuvered onto the side of the road, he just did, he just maneuvered. He just swerved around it and we continued on, I don’t know how he did that, it was so quick, it was quicker than a blink. And the thing I found amazing, there wasn’t the normal reaction when you’re in an incident on the road where you’re afraid it’s going to be bad. There was none of that, it was just absolute calm from him, total calm.

The first thing I did once we’d stopped talking, once there was a gap in our conversation, was I tuned in and I asked Spirit, my Higher Self, whatever you want to call it, what was that? I was told it was a recalibration of both of us, especially Bill – that the car did represent fear and that it was a step up to a new paradigm of thinking for both of us, basically, however you want to look at that, it was definitely a step up and away from fear.

I thought: Okay, let’s say that car represented fear, and we stepped to the side of it and around it and it didn’t bother us. Therefore, if ever I’m in a fearful moment in the future, I can reflect back on what happened and ask – how do I, like Bill did then when he swerved around the green car, how do I step around fear and not involve myself in it?

The lesson for me is to remember the moment and to say, I don’t need to have a head on collision because of fear, I can step around it.

In other words, don’t collide with fear, don’t headbutt it, don’t allow it to wash through you, just move aside from it. That’s hard, I’m not saying that’s easy, not saying that I’m going to be able to do that, but I’m saying that I have a template for doing it now, I have an experience that I will take forward as an example.

I remember that glorious moment after Bill swerved onto the shoulder of the road then he swerved back onto the road again and I thought to myself: Have we just died and we’re in heaven? Everything just looks so beautiful. The sun’s shining, the grass in the paddocks is green. I now realise that on the other side of fear, everything is bright and beautiful…

Jennifer Cluff -

Fear nearly killed us yesterday ~

Jennifer and I nearly died yesterday.

We were literally inches from death.

We were driving back to Mudgee from the Hunter Valley, where the previous night we’d screened the fine-cut of Facing Fear to a veteran film distributor.

(He loved it, by the way!)

We were on a two lane highway, and there was some traffic coming towards us.

Suddenly this car – this lime-green muscle car – went to overtake a truck in front. There was simply no room to overtake. Like, I mean, NO room.

When I saw this oncoming car edge out I thought – nah, surely the driver’s seen me and he or she is going to abort the overtake. But the car kept coming. Accelerating. It was traveling fast – probably 120 to 130kms/hr or so. And I was doing maybe 103km/hr.

This car was now barrelling straight towards us – like I say, fast – on my side of the road. I couldn’t believe it. There was no time to do anything other than to swerve onto the shoulder of the road. Which is what I did.

Fortunately there was enough shoulder to take the width of my car – but I was aware that I could very easily lose it in the loose gravel and go into a slide then roll.

But I kept calm.

I swung across, the green muscle car screamed past with only inches to spare between our two vehicles, and then I managed to swing back onto the road again – and the whole thing was over.

From the moment the car began to overtake to the moment it flashed past me was maybe five seconds, that’s all. Possibly even less. But I could be mistaken because it seemed as though time stood still.

There are a few interesting things about the whole bizarre episode.

For starters, the car was the exact same colour as my film on fear, Facing Fear. The exact same colour of green.

Facing Fear – Key Art Also, it was a muscle car and it was low to the ground and its engine growled and it was like an attack on us – this green growling bullet heading straight for us – its sole intent being to take us out.

Fear was attacking us.

I mean, overtaking like that, with absolutely no room to overtake – it made no sense. It was suicidal.

The other interesting thing was as this unfolded, I was calm. I didn’t panic, I didn’t freeze and go into fear – I quickly assessed that this was a life-or-death situation and I very calmly manoeuvred Jen and myself to safety then when the danger had passed I returned back to the road.

And I didn’t go into panic mode after the incident.

No adrenalin rush, no shaking or shortness of breath or any sign of delayed fear – nothing. I just kept on driving. Jennifer looked across at me and said: Have we just died and gone to heaven? I said to her: I’m not sure. Maybe.

I mean, how totally bizarre, the whole thing.

The coincidence of that car being the exact same colour as our artwork on the film is bizarre. Jennifer and I don’t buy into coincidences. And this coming straight after a successful screening of the film to one of Australia’s top distributors.

And the fact that this seemed like a deliberate, almost kamikaze type attack on us. I’ve driven a lot of miles in over fifty years of driving and I’ve never had an experience like that before.

Jennifer and I analysed it later and came to this conclusion:

The car represented fear, and it wanted me to experience fear, and had I experienced fear there’s no doubt that Jennifer and I would now no longer be alive. If I’d gone into fear I would have been incapable of taking the evasive action that I did – which required calmness, focus and steadiness.

So we faced fear and we didn’t succumb – and we’re here now still wondering why it happened…

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.